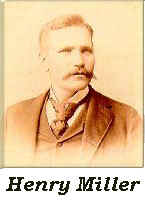

July 11, 2001 Henry Miller: IBEW's Founder Kindled a LegacyJuly 10, 2001 marks the anniversary of the untimely death of IBEW's founding President More than a century ago, one lineman who envisioned electrical workers united in common goal of brotherhood devoted his life to make it happen. Henry Miller's America was still a country of pioneers, only recently connected by advances like the continental railroad, the telephone and the advent of electricity. But Miller had the foresight and sense of purpose to weave his vision of a coast-to-coast Brotherhood that still thrives today. The very success of the industries that spurred the growth of the United States depended on the work of those who erected the power poles and connected the lines, risking-and often losing-their lives in a dangerous trade. So dangerous that Henry Miller, who contributed so much to the future safety of IBEW electricians-was killed 105 years ago. In the world he set out to change in the early 1890s, the electrical workers were earning pitifully low wages as employers hired only unskilled workers, undermining the reputation of the trade. Through the 1870s and 1880s, many small electrical unions formed and disappeared. Enter Henry Miller, a local lineman working at the 1890 St. Louis Exposition, featuring "a glorious display of electrical wonders." But as he spoke informally to his fellow tradesman, they found industry wide problems and concluded that in addition to exceptionally high mortality rates, they could earn no more than fifteen-to-twenty cents an hour for 12-hour days. Wiremen fared no better. Seeking to act collectively, they turned to the American Federation of Labor and chartered themselves as the Electrical Wiremen and Linemen's Union, No. 5221 of the AFL. Henry Miller was elected president. Recognizing immediately the organization had to be national to command any real bargaining power, he traveled the country spreading the word about the benefits of unionization. Everywhere he went, he organized the electrical workers he worked with into local unions. Among the locals chartered in those early years were in Chicago, Milwaukee, Indianapolis, New Orleans, Toledo, Pittsburgh, New York and other cities. The first secretary of our Brotherhood, J.T. Kelly said, "No man could have done more for our union in its first years than he did." On November 21, 1891, the first convention was called in St. Louis with 10 delegates representing 286 members. Meeting in a small room above Stolley's Dance Hall in a poor section of St. Louis, they drafted a constitution, laws and emblem -- a fist grasping lightning bolts. The National Brotherhood of Electrical Workers was born. Except with small changes to its wording, the constitution adopted in 1891 has been retained by every convention of the IBEW: "The objects of the International Brotherhood of Electrical Workers are: to organize all workers in the entire electrical industry in the United States and Canada, including all those in public utilities and electrical manufacturing, into local unions; to promote reasonable methods of work; to cultivate feelings of friendship among those in our industry; to settle all disputes between employers and employees by arbitration (if possible); to assist each-other in sickness and distress; to secure employment; to reduce the hours of daily labor; to secure adequate pay for our work; to seek a higher and higher standard of living; to seek security for the individual; and by legal and proper means to elevate the moral, intellectual and social conditions of our members, their families and dependents, in the interest of a higher standard of citizenship." Born humbly with a $100 loan from the St. Louis local, the NBEW was chartered by the AFL in December 1891, giving the organization sweeping jurisdiction over electrical workers in every branch of the industry. In the early years, a group of telephone operators joined, becoming the NBEW's first women members. And The Electrical Worker, the Journal's predecessor, began publishing in 1893. Through the 1890s, unsafe working conditions and substandard wages prevailed, but the adoption of an apprenticeship system promised a better future for the industry. In 1895, when the roll was called at the Fourth Convention in Washington, DC, only 12 delegates answered. The treasury was in debt more than $1,000. The strength and determination of the union's early officers and members were the only forces keeping the organization alive. After Henry Miller died, when an electric shock caused him to fall from a pole on July 10, 1896, J.T. Kelly wrote of him: "He was generous, unselfish and devoted himself to the task of organizing the electrical workers with an energy that brooked no failure." That devotion to the task of organizing, that capacity to turn plans into action, to change a dream of unity and bargaining power into the reality of the Brotherhood, leaves all union members indebted to the legacy of Henry Miller.

|

"Henry Miller, aged forty-three, the head lineman in the employ of the Potomac Light and Power Company, fell from a pole last evening about 11:30 o'clock on Newark avenue near Tenleytown road, in the Cleveland Park subdivision, and died from injuries after suffering for nearly five hours." Evening Star, Saturday, July 11, 1896, p. 21 |